Web of Lies

Fake News’ (n.)

False, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news

Caught in the net of the online world

Terrors of the internet can hurt us any day, any time. There are click farms, creeping bots, and fake news, oh my! The internet’s icky underbelly threatens to covertly siphon our bank accounts, misdirect marketing money through ad fraud, use fear and love to swindle, and even buy up tickets to events we want to go to, forcing us to pay scalpers.

We explore the internet’s dark side.

The phrase “fake news”—oft thrown around by U.S. President Donald Trump—has barged into our lexicon to the degree that Collins Dictionary named it Word of the Year in 2017.

The Okanagan Valley is not immune to the cynicism next door.

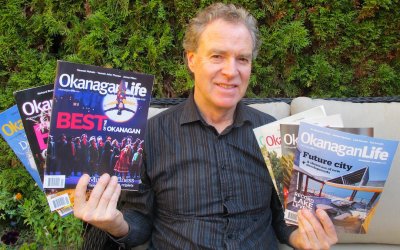

CBC Daybreak morning show radio host Chris Walker (photo) says Okanagan news organizations have certainly suffered from the fake news chorus. Local listeners have become more skeptical, and municipal politicians have become more emboldened to flirt with truth.

“The trust in journalistic institutions is being shaken. People are more skeptical,” he says, adding “that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

A troubling consequence, however, is that skepticism can quickly turn into animosity.

“I’m seeing it certainly in my interactions with the public. There are people who are dismissive of the CBC and of journalists in general. You know the kinds of things we hear from south of the border, and more and more Canadians believe those things. These countries are so intertwined in terms of our culture and our politics that it’s inevitable there’s going to be an effect in Canada.”

Walker says it’s important that newsrooms stand on guard by ensuring audiences can verify that news content is credible. They can do that by adding bylines, corrections when warranted, and clear references and sources. Like the ingredients on the back of a peanut butter jar, people need to know what’s in their news.

“This is important for the functioning of our democracy,” says Walker. “If we want to solve the problems that we have in our communities, in our province, in our country, and in our world, we need to do that on the basis of good information.”

Few things in the world are free. Good journalism costs money, and many media organizations have suffered tremendous cutbacks. There are fewer journalists covering fewer stories. Yet it doesn’t cost a cent to reprint a press release on a website, says Walker, who acknowledged the CBC has the advantage of not having to compete for ad revenue.

Still, most local publications don’t have public funding to draw from. And ad revenue is—at least in part—tied to audience. News can be a tough sell.

“We’re competing against the latest viral video of a seal smacking someone with an octopus. But there’s only so many eyeballs and so many minutes in a day that somebody has to consume information. If we’re competing with a juggling walrus, it’s difficult.”

That’s why trustworthy, honest data detailing website clicks and digital impressions are key.

A first impression

When it comes to online ad fraud, many businesses in the Okanagan—and around the world—have been impacted.

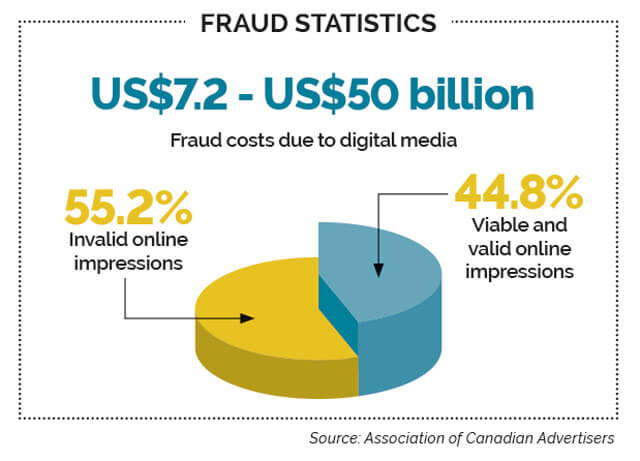

A recent report into advertising fraud by the Association of Canadian Advertisers (ACA) sought to identify “the breadth and depth” of invalid traffic—a term that basically means ads are being shown to machines, and not people. You often hear them referred to as “bots.”

The study, called The Bottom Line on Bot Fraud, states fake traffic is a significant global problem.

[downloads ids=”159043″]

Not only are marketers’ budgets vulnerable to criminals who exploit the digital media supply chain, but their digital marketing metrics can also be compromised,” said the report.

This kind of fraud costs between US$7.2 billion and US$50 billion, depending on who you ask. The study found only 44.8 percent of online impressions were “viewable and valid.” The invalid views were mainly due to off-screen browsers and non-human data centre traffic.

UBC-Okanagan Assistant Professor of Marketing Eric Li says with the shift online, advertisers are using unfamiliar platforms and are looking closely at their return on investment—and not always seeing results.

UBC-Okanagan Assistant Professor of Marketing Eric Li says with the shift online, advertisers are using unfamiliar platforms and are looking closely at their return on investment—and not always seeing results.

“If you opened up your Facebook page I can guarantee at least five ads. You pay money but you don’t see the impact,” he says. “It’s not a super safe place for doing business because of the hacker culture that is there,” he says.

Li says actions being taken to combat ad fraud are increased security checks and direct compensation.

Advertisers want to see people clicking on, and buying, their products; they want the creation of a community to talk about their campaign or brand. The best strategy to maximize results is to broaden your marketing strategy and try to pull people into your campaign, he says. Generally, marketers have to be more creative.

“If you opened up your Facebook page I can guarantee at least five ads. You pay money but you don’t see the impact,” he says. “It’s not a super safe place for doing business because of the hacker culture that is there.”

How does ad fraud impact the average Jane and Joe? Well, your tax dollars are at risk.

Digital ad spending—through channels like Facebook, Twitter and search engine ads—by all levels of governments has taken an increasingly larger share of the advertising pie. The 2016-2017 federal annual report on advertising activities shows digital spending rising steadily from 20 percent of the ad budget in 2012 to the lion’s share of 55 percent in 2017. Social media ad spending on Canada 150 alone cost taxpayers nearly $2 million.

Social media is big business. To give you an idea of how big, Twitter recently said its total advertising revenue reached $650 million in Q3 of 2018, an increase of 29 percent year-over-year, and reflecting growth across most products and geographies.

Every little bit adds up for the international giants.

Locally, the City of Kelowna said it spends about $8,000 a year on social media advertising, including the airport’s social media advertising. They mostly target Facebook and Instagram, where they propose to have a broad reach.

It works out to pennies per post, said the city, based on the number of people the ads reach.

It’s not just advertisers who are at risk. Fraud on the internet hits home.

Burned by love

You can’t get much more personal than love.

Last year, a Nanaimo woman lost $15,000 through a Facebook scam that started as romance. The woman, identified only as 67-year-old ‘Mary,’ had received a Facebook message from a man, who went by the name of ‘Kevin.’ He claimed to be a high-ranking officer with U.S. Armed Forces stationed in Turkey.

Their exchanges became personal, and two months into the affair, he proposed. They made plans to move to Florida when he returned from his deployment.

But Kevin soon needed financial help. A friend’s wife needed emergency surgery and he asked Mary to help pay for the operation.

“Without blinking an eye, Mary went to her local chartered bank and withdrew what she could and wired it to Kevin,” said police.

Other problems popped up, and Mary continued to be generous.

Then Kevin disappeared from her Facebook friends list, leaving Mary with a decimated bank account and a broken heart.

Mary was planning to retire, but has since opted to work longer to recoup some loses.

“A simple Google search would have revealed the scheme he was using has been carried out hundreds of other times worldwide,” said police.

Even vigilant people are losing thousands of dollars in online fraud.

Even vigilant people are losing thousands of dollars in online fraud.

Okanagan resident Anna Jacyszyn has experienced what it’s like to lose a lot of money overnight. A few years ago, she had $10,000 siphoned out of her bank account, including ticket revenue from the jazz singer’s performances and her personal savings.

Jacyszyn made the discovery after trying to take out money to pay rent and pay her band members.

“It’s very scary to know that your accounts can be deleted in an instant,” she says. She did manage to get most of the money back through the bank’s investigation into the theft.

No one is safe

According to Interac, almost one quarter of Canadians have clicked on a phishing link. The company conducted a survey earlier this year that found online payment fraud, like phishing, is a growing trend, and Canadians are worried about it.

Phishing is a scam where fraudsters attempt to acquire personal or financial information, such as passwords or card numbers, by masquerading as a trustworthy person or business through electronic communications. It is typically carried out using e-mail or an instant message, although phone contact has been used as well.

Interac found that two-thirds of people across all age groups report they have been tempted to click on a link they weren’t completely sure was safe. “This uncertainty is putting Canadians at risk,” said Interac.

The federal government is taking steps to punish cybercrime. This year, Canada imposed sanctions against the installation of malicious software through online advertising for the first time in its history.

The federal agency used Canadian anti-spam legislation that came into effect in 2014, known as CASL (spoken as ‘castle’), to issue a notice of violation, including penalties of $100,000 to the Ontario company Datablocks and $150,000 to Sunlight Media based in Los Angeles.

The CRTC said that through their actions and omissions, Datablocks and Sunlight Media aided in the installation of a computer program on another person’s computer system without the express consent of the owner or an authorized user of the computer system.

Darkness and light

Notifications pop up on our phone in a relentless drone: news headlines, social media notifications, regular interruptions. Is there a deeper spiritual cost to all this digital connectivity? How can one be still and know?

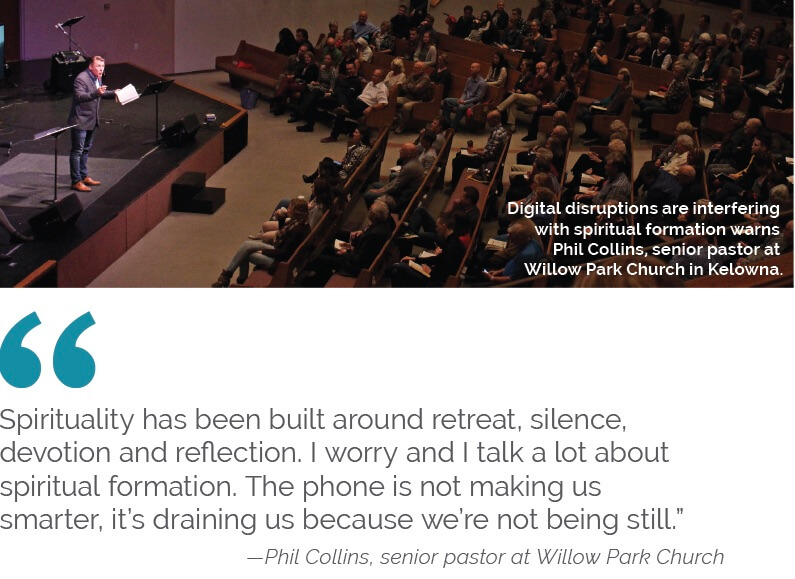

Phil Collins, senior pastor at Willow Park Church in Kelowna, says the conversation about social media comes up often. Many people, particularly millennials, engage through social media.

“I’m in the coffee shop yesterday, and three guys are in the coffee shop together, talking to each other through their phones and laughing,” he says.

Spirituality has been built around retreat, silence, devotion and reflection, but people can’t do that as effectively nowadays, he says.

“There’s always a notification and a ping that interrupts them. I worry and I talk a lot about spiritual formation. The phone is not making us smarter, it’s draining us because we’re not being still,” he says.

People can also fall into a pattern of conflicting values. Collins cites internet pornography as an ever-present concern. Generous and trusting people can be taken advantage of by wolves, he says.

“It’s not just church people?—?it’s vulnerable people looking for companionship. That comes through my world a lot,” he says. “You have to look at the facts and not the emotion. If it’s too good to be true, it probably isn’t true. Everybody is looking for Prince Charming or Princess Charming. Naive people are in danger of being exploited.”

Collins says it feels like there’s very little that can be done through the legal system because it’s global and very difficult for police to enforce.

He says it’s important for spiritual leaders to shine a light in the darkness.

“I think our goal is to engage in social media to show the authenticity of our lives, to show issues that are important and to spiritually shepherd people through digital means. It’s a medium which we can use beautifully to encourage people through their faith journey,” he says.

For example, Collins uses his digital presence to help people cope with anxiety and stress. He’s put out more than 20 segments that are available online.

“We have to be prolific in our content. It has to be beyond the selfie and it has to be meaningful. Let’s be honest and let’s add value to people’s lives so what we put out there has substance.”

As seen in

[downloads ids="156027" columns="1" excerpt="no"] WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR AD FRAUD?

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR AD FRAUD?

That’s a multi-million-dollar question. Publishing Executive magazine went so far as to call it a mystery wrapped in an enigma. It’s a global problem, but who exactly is causing it?

We know who profits: fat-cat Wall Street bankers and advertising agencies, while politicians can’t (or won’t) do anything to stop it.

We know who suffers: advertisers and publishers. Companies are fighting back. Procter & Gamble Co. cut its spending on digital advertising by more than $200 million last year, according to the Wall Street Journal.

The corporate giant, which owns brands like Crest, Tide and Pampers, said the spending had been largely wasteful and that it was reaching its customers in more effective ways.

The Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce report Cyber Assault: It should keep you up at night reveals that millions of Canadians have been preyed upon — “leaching money and intimate, personal data that will live on the internet forever.” The report accuses the federal government of failing to protect Canadians from increasingly sophisticated cyber-attacks. In 2017, 10 million Canadians had their personal information compromised.

Bad bots make up a fifth of all web traffic, says Distil Networks. Those bots are responsible for digital ad fraud. In 2017, bad bots accounted for over 20 percent of all website traffic, a nearly 10 percent increase over the previous year. Good bots increased by 8.7 percent to make up 20 percent of all website traffic.

0 Comments