Study links specific chromosome to radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis

A UBC Okanagan researcher has determined that genes on a specific chromosome may be the answer as to why thoracic radiotherapy leads to a lung injury in some lung cancer patients.

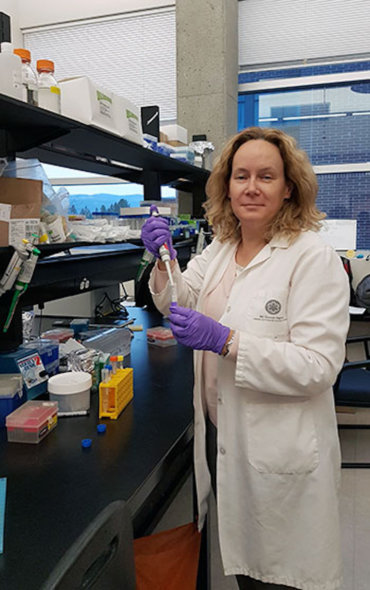

Christina Haston, an associate professor of medical physics, recently published a study examining how chromosome 6 can contribute to radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Her study finds that genetic differences can determine whether or not this lung injury follows radiotherapy in an experimental system.

“Currently, 50 percent of cancer patients in Canada receive radiation therapy as part of their treatment course,” she says. “In addition to effects on the tumor, up to 30 percent of these patients develop side effects to this treatment or injuries to non-tumor tissue.”

Pulmonary fibrosis is a progressive disease related to damaged lung tissue, making it difficult for patients to breathe and process oxygen effectively. Some lung cancer patients have developed pulmonary fibrosis after radiation, while patients with other cancers have developed it after receiving a specific cancer medication called Bleomycin.

“One of the limiting side effects of thoracic radiotherapy is the development of pulmonary fibrosis, in a susceptible subpopulation of treated patients,” says Haston. “However, the specific pathways contributing to fibrosis susceptibility in radiotherapy patients remain unidentified.”

It has been thought that white blood cells, the body’s natural defense mechanism, may contribute to pulmonary fibrosis. Building on this, her research has drawn a connection of chromosome 6 genes to fibrosis susceptibility.

She examined the susceptibility to pulmonary fibrosis on lab mice after radiation therapy and on mice after treatment of Bleomycin. The mice with a replaced chromosome 6 were protected from both radiation-induced and Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis.

“The recent findings by our lab have specifically identified these genetic differences to reside on chromosome 6,” she adds, explaining that her work may open the door to individualized cancer treatments depending on a person’s specific genetic makeup.

Her study, published in Radiation Research, was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“This research aims to develop a pre-treatment marker based on knowledge of specific genes of radiation injury response,” she adds. “Such a marker could significantly affect Canadians with cancer, by sparing side effects and increasing the dose to a tumor which may, in turn, increase cure rates.”

About UBC’s Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning in the heart of British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley. Ranked among the top 20 public universities in the world, UBC is home to bold thinking and discoveries that make a difference. Established in 2005, the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world.

To find out more, visit: ok.ubc.ca.

0 Comments