Cultivating the cannabis industry

Cultivating the cannabis industry

The business of legalizing marijuana is creating a buzz in the Okanagan. Whether you call it pot, weed or Mary Jane, cannabis becomes legal across Canada on July 1, 2018, when the federal government officially enacts Bill C-45.

The new cannabis law will end almost 100 years of prohibition.

Expect the weed scene to become as mainstream as the bar scene. People will smoke different sativa and indica strains with catchy names like Pineapple Express, Blue Dream and Super Silver Haze. Buds and confectionaries will sell online and through retail.

The machine of legalization will build a multi-billion-dollar industry, spawning industrial grow-ops, dispensaries and a myriad of products.

It’s a seismic economic shift—a marijuana industrial revolution.

Many are betting on just how much the Okanagan could be under the influence, wondering if over time, pot can overshadow the region’s wine industry?

As seen in

[downloads ids=”148995″ columns=”1″]

Supply

Supply

The non-descript white building nestled in a West Kelowna industrial area is completely surrounded by chain-link fence. There’s no way to tell it’s one of Canada’s approximately 65 legal marijuana production facilities—not even a sign with the company’s name on it.

Inside, the appearance is plain. White walls, white doors.

Doja Cannabis Co. founder Trent Kitsch looks more like a surgeon than a pot grower. He’s wearing a surgical facemask, thick latex gloves, a hairnet, rubber boots and a white jumpsuit. These sanitary measures ensure no outside impurities taint the pot plants.

The operation, one of Canada’s approximately 65 legal marijuana production facilities, has been a long time coming. Health Canada’s process to win a growing licence has taken Kitsch and his team more than 1,400 days, after first applying in 2013.

“Much of that time we were investing on a hope and prayer that it was going to come to a licence,” he says. “We would have never imagined when we started that recreational cannabis was also going to be part of the future.”

However, the federal Liberal Party is making good on its promise in the 2015 federal election to legalize marijuana.

“I was there when Justin Trudeau announced in (Kelowna) City Park that he wasn’t just for decriminalization. He was for legalization,” says Kitsch. “I was very proud to be there, and also excited to be in a country that is as open minded as Canada, and as innovative as Canada and as forward-thinking as Canada.”

To enter the heart of the grow-operation, Kitsch swipes his key card.

It’s like a maze and it feels disorienting. Fans, lights and other equipment create a constant hum.

Different doors lead in many directions, all secured. Each visitor to each individual room chirps their key card to create a detailed record of who has been where and when. Almost 100 cameras watch everything throughout the building.

We enter one of three grow rooms, filled with tall, budding, plants. The air is humid.

Kitsch says the plants are currently sleeping, so the bright hydroponic lights are turned off. The snoozing plants bathe in gentle green light.

In the mother room, plants are bred and crossed. In the nursery, seedlings are whisked quickly into adulthood.

The room where the valuable buds dry is still empty, as the young company is yet to complete its first harvest. After drying, staff will move the buds into another room for trimming, packaging and labelling and then store the final product in a massive vault built to keep millions of dollars of pot safe.

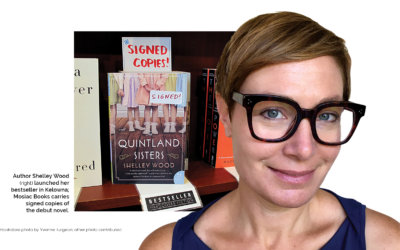

Founder Trent Kitsch offers coffee and cannabis education at Doha Cultural Cafe. Photo: David Wylie

You could classify Kitsch as a serial entrepreneur. He has gone from pro-baseball, to founding successful underwear company SAXX, to real estate and construction, to establishing a winery, and now producing marijuana.

“The first time I had an ‘A-ha!’ moment was in 2004,” he says.

Playing professional baseball as a back-catcher, Kitsch made it as far as being invited to a big-league training camp. With regular drug testing in his sport, he never really used pot.

After his baseball life, Kitsch worked in the Caribbean, surrounded by Rastafarian culture. He learned to see marijuana in a different light, almost as a sort of ritual. He’d go to a reef and smoke and watch the sun set. Time seemed to slow, and he meditated and refocused his mind.

Back in the Okanagan, Kitsch found another benefit to the plant. Working on a construction site, he lifted too much weight and he pinched a nerve in his lower back. At first, he was prescribed OxyContin for the pain, but found it far too strong. A prescription for medical marijuana brought relief.

He opened the Doja Cultural Café, a coffee shop in downtown Kelowna, to showcase his brand and talk to people about cannabis.

“I think it’s really ground-breaking and historic what’s happening right now. We’re trying to have the Okanagan rally behind us and rally around us. I think it can be as large, or larger, than the wine industry. It just needs to be professionally and legally represented.”

Demand

Demand

Kyla Williams was born Feb. 1, 2012.

At the time she appeared to be completely normal, her family says. But at three months they noticed upper eye movement and a slowdown in her development. By six months she was referred to a pediatrician who immediately recognized symptoms of epilepsy.

Kyla spent time in Vancouver Children’s Hospital, undergoing a barrage of tests. No explanation surfaced and symptoms escalated relentlessly.

Courtney treated her daughter Kyla with cannabis oil to reduce non-stop seizures (here in the arms of grandmother Elaine Nuessler.)

Family members had heard about an alternative therapy, a high-CBD low-THC form of medical cannabis, used in Colorado by many kids with epilepsy. They asked hospital staff about it, but medical marijuana was then illegal and not available in Canada. No clinical trials were on the horizon.

By February 2014, Kyla had seizures non-stop all day. She was suffering and declining quickly.

Kyla’s grandmother, Elaine Nuessler, said the family needed a solution—and fast. But to give her cannabis oil?

Nuessler never had any interest in marijuana, or drugs. In fact, her husband Chris, a retired RCMP officer, spent his career fighting illegal substances. (Top photo by Yvonne Turgeon)

Now, she and her family found themselves in a position where they’d have to break the law to try a medical treatment.

With the cannabis extract, Kyla started to get better, like other children had.

“I’m not going to say it’s a miracle, but it certainly has given these children a quality of life,” she says. “We were amazed what we were able to achieve with her seizure control.”

The stigma at the time was strong. As conversation around decriminalizing marijuana intensified, opinion was vocal and split.

The family decided to go public.

“We tried to protect ourselves a little bit by coming out in the media,” said Elaine.

People started gravitating toward Elaine and she began advising seniors and those with young children in medical crisis about her experience.

Today their days are spent at their new shop in Summerland, Purple Hemp Co. selling essential oils, soaps, hemp clothing, yarn and other products and raising awareness about the uses of the plant.

“We’re taking the soft approach,” she says. She couldn’t be happier with the direction Canada has gone.

“Look at how far we’ve come. I never thought we would be at this point, at the precipice of legalization. I hope it’s done right.”

As seen in

[downloads ids=”148995″]

Retail

Retail

Opposition is still vocal, with groups lobbying about everything from health and social to ethical concerns. Dispensaries have been a lightning rod for debate—and a thorn in the side for City Hall, as officials try to figure out how to deal with local licensing.

In Vernon, Imre Kovacs owner of The Herbal-Health Centre (THHC) is marking 15 years in the pot business. With interests in other dispensaries as well as distribution, his involvement spans from seed to retail. (Top photo by David Wylie)

“When the dispensary opened that started to change things for me. The retail environment is very front-facing,” he says.

The business became a focal point in the community, including in the media. So he began establishing relationships with officials in government and law enforcement, at one point hiring former mayor Wayne Lippert as a consultant to facilitate relationships.

“It was constructive,” says Kovacs, saying officials had a lot of questions around quality assurance and security.

“We really wanted to demonstrate how this business could and should be done, and be a model for the entire industry and for governments at all levels to see.”

He says quality assurance is similar to what you’d see in a pharmacy, even with independent lab tests to look for residual solvents, as well as determine potency—which can help adjust dosage in value-added products like edibles and oils.

Like in a pharmacy, staff consults on side effects, dietary changes to be expected, and other issues.

The company also pays taxes like any other.

“We’re audit-friendly, we’re not at all a cash-business and we do run as a for-profit business. All of our accounting is transparent and on the books,” he says. “That’s how we’ve been operating for four years.”

The company is ready for the industry to legitimize next year. But just how that will all pan out is still hazy.

Each province will legislate its own policies. In Ontario, the government will control marijuana through a control board. Alberta is expected to go with private stores, as is BC.

“The fact is, if they don’t provide a transitory pathway for the existing market—those who are currently in the industry and in many cases in the industry generationally—to participate in a legitimized cannabis economy, then they’ll just keep doing what they’re doing, very happily,” says Kovacs. “We’ll continue to have a very powerful and established underground economy which will absolutely undermine any regulatory efforts that provincial or federal governments make.”

Doja cannabis facility. Photo contributed.

Commercial

The stakes are high.

In Colorado, marijuana is already worth more than $1 billion-a-year—and it took only eight months of 2017 to hit that mark.

A recent Deloitte Canada report says sales of recreational marijuana alone could be as much as $5 billion per year to start in this country, a number on par with the Canadian spirits market (whiskey, vodka, rum, etc.)

Add in support businesses, like security and transportation, and the potential economic impact approaches $23 billion.

None of this accounts for things like taxes, licensing fees, tourism and paraphernalia sales.

For Steve Harvey, CEO of Business Finders Canada, the marked impact on the Okanagan’s commercial real estate market is already showing.

“Large facilities are needed to grow and store marijuana, so industrial warehouse owners have seen rental rates and property sales spike,” he says.

It’s estimated cannabis production will require more than 10 million sq. ft. of production space in Canada. Harvey is already working with licensed producers to find properties in a market feeling the pinch of tight supply.

“This has the potential to be one of the fastest growing industries around.”

0 Comments