Long before you spot him among the crowd you might hear Chuck Fipke laugh. A delighted kind of a cackle, its an unbridled and boisterous display of pleasure as unique as the man himself.

Canada’s most decorated discoverer of diamonds—and one of the most renowned geologists in the world—relishes good friends, good food and wine, good racehorses and of course, good, mineral-rich ground.

Once an undaunted scientist living out of his car in the Northwest Territories, collecting samples to be baked back home in his oven, Charles Fipke made history with the discovery that led to Canada’s first surface and underground diamond mine—Ekati—northeast of Yellowknife, in 1998.

While the polar bear emblazoned gems have made him a legend in geologists’ circles, it’s Chuck’s contributions to his alma mater, the University of British Columbia, that have endeared him locally.

Already a benefactor extraordinaire, donating millions of dollars to UBC Okanagan, Chuck recently put his money where the microscope is.

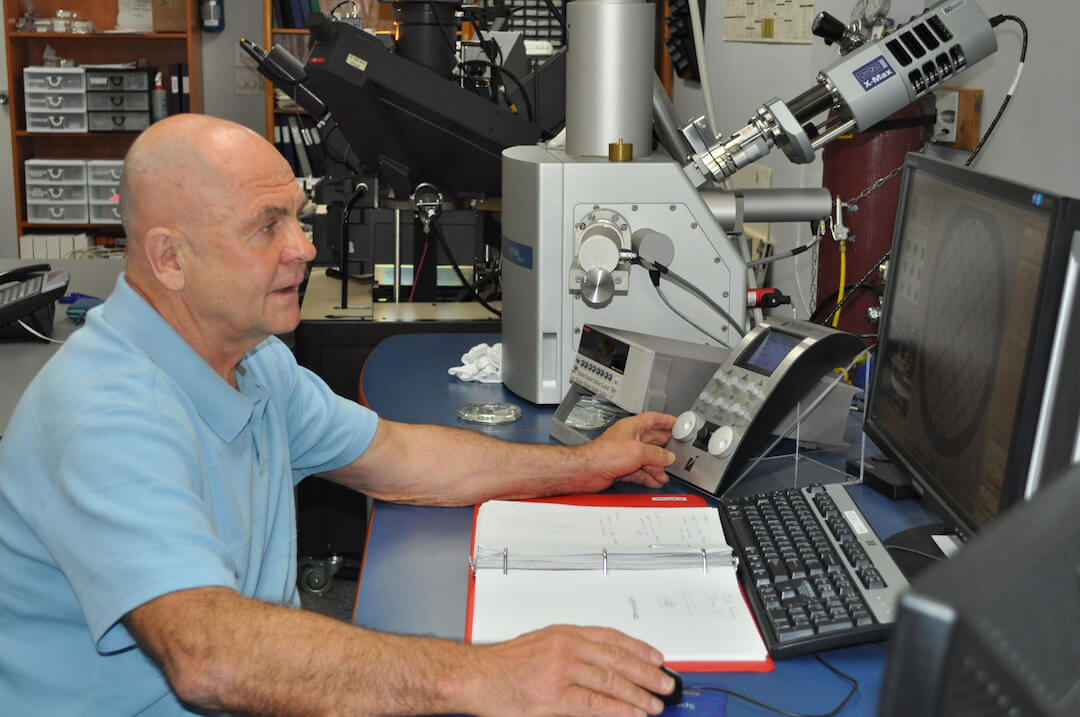

“I’ve donated a laser ablation ICP mass spectrometer,” he says, the name of the sophisticated science equipment already invoking awe. “Then I donated a scanning electron microscope with a new type of head that allows the microscope to achieve one micron resolution.”

The capacity of this kind of equipment is intricate, applicable not only to geology (the powerful microscope can detect all of the elements in a substance, while the electron microprobe analyses findings) but biology too, aiding in medical research for viruses.

The gorgeous glass building bearing his name—the Charles E. Fipke Centre for Innovative Research—clearly announces Chuck’s extensive contributions to UBC Okanagan but what is not so apparent is this accomplished man’s humble history.

“I’d prefer my donations to be anonymous,” he quietly explains, gazing out at Okanagan Lake, lapping at his beach house shore, “But I’ve been cast into the position of a role model, particularly to young geologists.”

He relays a story of when he first became famous, when the Ekati mine was sparking headlines. The men’s magazine, Maxim, (more substance than sexy in those days) approached him looking for an interview, but at first he declined. “Why?” he says with a shrug. “I had no real reason to do the interview. I really wasn’t that interested.”

That is until his eldest son pointed out what came to prophesy Chuck’s future philosophy. “My son told me that we live in an apathetic society and what people need is someone to look up to.”

That got Chuck thinking and remembering his own role models; the men who had, through hard work and determination, not to mention selfless generosity, inspired a young Charles to challenge himself and ultimately to give back.

After graduating from Kelowna Secondary School, Chuck went on to study geology at UBC in Vancouver. Married with a baby, at one point he was nearly forced to quit school.

“I was totally busted broke,” he says. “So I made an appointment with dean Walter Gage, asking him if there were any bursaries, scholarships, anything I could apply for.”

With only two months left in the school year, the dean informed Chuck that kind of funding was finished but then Walter Gage (after whom a residence and library are named) did something incredible. “He asked me how much I needed. I told him two or three hundred dollars,” Chuck explains. “He opened his desk drawer and pulled out his personal cheque book.”

Did that generous act ultimately give rise to one of the most stunning mineral discoveries of our time? Who knows, but it certainly inspired Chuck to—quite literally—pay it forward.

“A few years ago, former premier, Bill Bennett, asked me to donate to a professor at UBC Vancouver who was doing research with aspirin and Alzheimer’s. I wanted to but I got busy and put it aside.” He pauses, a saddened look on his face. “Then last Christmas his son, Brad, attended my company party and I asked after his dad.” Chuck was stricken when he learned that Bill was suffering from dementia. “I felt terrible. There was an urgency there that I didn’t act on. So many great minds have suffered from this disease.”

With a recent contribution of three million dollars toward that research, Chuck hopes to make up for lost time.

“I would have nothing if it weren’t for my education,” he says. “I’m privileged to give back.” ~Shannon Linden

Photo by Paul Linden