I call him Collard. He’s a gorgeous hunk of piano, an 1864 product of the British piano maker Collard and Collard Company. When we met, the choice was this parlour grand or a molar implant. I don’t miss the tooth.

I speak of Collard as a living entity because in many ways, he is. His character and appearance are unique. He has his own room. He’s responsive to touch and satisfies my legato longing. Besides, we make beautiful music together. I’m in love.

Barbara Shave

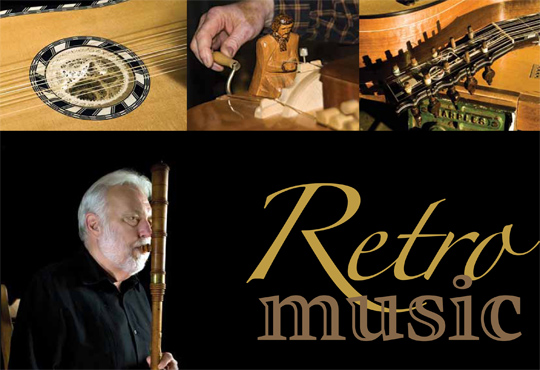

Through Collard’s connections, I’ve learned of a close community of locals who conserve, craft and collect an astonishing variety of weird and wonderful musical instruments while recreating their equally weird and wonderful sounds.

I’m talking about harpsichords and hurdy-gurdies, viola da gambas and vihuelas, about banduras, balalaikas and bouzoukis. I’m talking about curtals and even odder things. The names of these instruments intrigue me as much as their appearance, history and sound.

Period instruments are classified by era: Medieval (before 1450), Renaissance (1450-1600), Baroque (1600-1750), Classical (1750-1825) and Romantic (1825-1900). You’ll note that Collard is officially a Romantic. That’s not my imagination.

All sizes, shapes and ethnicities are further defined. The concert instruments with orchestral adaptations and written scores are mostly Western European. Folk instruments generally have ethnic associations but no written traditions.

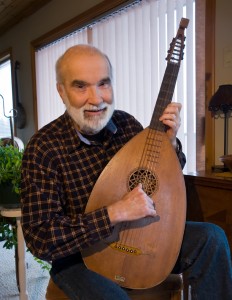

Felix Possak

Felix Possak, who makes his home in Peachland, must set some record for private ownership of stringed folk instruments. If you’ve taken a Kettle Valley Steam Railway excursion, you’ve met Felix, the congenial sing-along fellow. From Vienna, the city of music, he was swept away by the Kingston Trio in 1966 when he hung out with American students at the university and adopted the guitar and banjo.

After moving to Canada in 1967, Felix toured the Maritimes with an Irish group. Into the 1980s, his Banjo Palace Band was a fixture at conventions and grandstand shows across the nation. Felix even pulled together 15 concert musicians to tour with a Viennese orchestra.

All the while, he’s been collecting stringed folk instruments. At last count he owns a violin, two autoharps and numerous mandolins. He also has two classical guitars, a guitar lute and a harp guitar, which has two necks with separate sets of strings. When he pulls out his rare ukelin, it lies across his lap and he uses a bow to play its 16 strings.

Felix’s hurdy-gurdy could be called a mechanical cello. But where a cellist drags a bow across the strings, a hurdy-gurdy player uses a right-hand crank to turn an internal, resin-coated wheel that rubs the strings continuously producing a drone like a bagpipe. Left-hand levers adjust the pitch.

His Ukrainian bandura is a huge lute with about 50 strings, while his long-necked, bulb-bodied Greek bouzouki, played with a pick, sounds metallic. Think Zorba the Greek. Russian balalaikas are triangular and three-stringed. Felix has the regular size and a granddaddy called a domra. The haunting quaver of balalaika music is often associated with Dr. Zhivago.

Felix is nearly always pictured with one of his seven American banjos. With strings basically stretched across a tambourine, banjos combine features of both string and percussion instruments. His oldest was probably used in one of the minstrel shows that popularized banjos over a century ago.

Felix shifts from one instrument to the next with hardly a break in the melody, remarking with wry understatement that he achieved this mastery with “a lot of practice.”

His collection also includes two lap dulcimers. Medieval in origin, this instrument is still associated with Appalachian folk music. Players pluck or strum the strings with a feather quill in the right hand while the left positions a rod on the struts to change pitch. The folk dulcimer was the forerunner of the harpsichord.

Harpsichord strings are also plucked via keyboard action, sometimes with feather quills but more frequently now with a plastic plectrum. Harpsichords are the only instruments that can accurately reproduce 18th century music. Bach (1685-1750) and Mozart (1756-1791) composed works that raced all over the harpsichord keyboard.

Susan Adams

In the Valley, when a harpsichord is set on stage for an Okanagan Symphony Orchestra (OSO) concert, Susan Adams is at the keyboard. She personally owns two replicas. The Italian is based on a 1694 original in the Smithsonian Institute. Its keys are colour-reversed, with the dominant naturals in black and the narrower accidentals in white.

Before keyboard standardization, keys varied in number, shape and size. Susan’s harpsichord keys are shorter and wider than those on her pianos. “At first I was grabbing handfuls of wrong notes,” she admits.

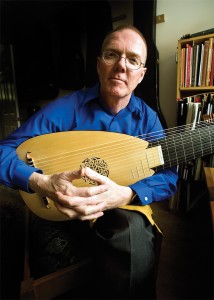

Clive Titmuss

Her 1769, French model, with double keyboard, was built from a kit by her partner, Clive Titmuss. An artist painted delicate Alberta wild roses on its soundboard. “She’s adorable, irresistible,” I say, thinking to myself, “She’s a French floozy and the less Collard knows about this little harpsi, the better!”

Susan also collects pianos, which she refers to by the formal term—pianofortes—meaning “soft-loud” in reference to the instrument’s ability to produce both soft and loud tones, while the harpsichord is limited to just one dynamic for each string. Of her three pianos, the Broadwood is her pride. An 1809 original, it is virtually identical to one given to Beethoven in 1817. Unlike today’s pianos, this instrument has a double-damping mechanism, making it possible to play sustained tones on part of the keyboard while pecking staccato tones on the other. Because Beethoven composed his piano sonatas on this kind of instrument, his music cannot be authentically replicated on any other. Susan’s Broadwood was in pieces when it was discovered, but former Peachland resident, Marinus Van Prattenburg accomplished a complete restoration. Marinus was Collard’s doctor too.

Another noteworthy keyboard instrument is the old pipe organ at St. Saviour’s Anglican Church in Penticton, which also attracts harpsichordists. McGill music graduate, Christine Purvis retired hers when she moved to Oliver and became music director and organist for the church. She describes that pipe organ as “the king of instruments.” Really a series of massive wooden flutes, a different length and diameter for each tone, it produces sound when a bellows delivers the necessary air that the player keyboards to the appropriate flutes.

Harold Lupton is remembered around Penticton for his years playing the St. Saviour’s organ. He’s also remembered for the harpsichords he built at home and his musical legacy links him to another Pentictonite, Ron Wall.

Ron Wall

Ron loves Celtic folk music and the instruments that produce those lively, River Dance sounds. “Celtic” is the term used to describe the common cultural origins of predominantly Western Europeans. The popular revival of Irish, Scottish and French folk music, with its echoes in Eastern Canada, necessitated a commercial identity and Celtic is the most common term. With the same common beginnings, country and western, bluegrass, Cajun and Métis fiddling all share historical connections.

Ron’s love of the music is so elemental that he was moved to build Celtic harps and over 20 years has constructed close to 200 in various sizes. These harps make key changes by hand-operated levers, which pinch and shorten the vibrating length of independent strings. In contrast, the pedal, symphony or classical harp uses a number of foot pedals to raise or lower the pitch of each of the seven musical notes in groups.

Felix Possak has a lever harp. So does Ingrid Shellenberg. In fact, she owns 16 harps ranging from one to two metres in height. She operates La Muse Harp Studio near Penticton and plays pedal harp with the OSO.

Ingrid Shellenberg

It’s no easy matter to transport such an instrument. Besides size and awkward dimensions, it also has 2,000 moving metal parts, which are easily damaged and ultra-sensitive to temperature change. Consequently, Ingrid’s prized 1913 gilded Lyon and Healy never leaves home.

Back to Ron and his connection with Harold Lupton. Harold’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Lupton, is Ron’s partner and a core member of the OSO. Inheriting her grandfather’s reverence for period instruments, Elizabeth’s joy is the Baroque violin that she has played for recordings and performances with period music groups such as Toronto’s Tafelmusik, Winnipeg’s Musick Barock, Pacific Baroque of Vancouver and the South Okanagan’s Masterworks Ensemble.

Crafted by English luthier, Kai Thomas Roth, and on loan from the Douglas Kuhl Foundation, this instrument has a shorter fingerboard than her modern violin and lacks both chin and shoulder rests. The strings are gut rather than metal and the bow is slightly shorter with a convex curve. She describes the tone as “dark honey.”

Elizabeth Lupton

Elizabeth co-directs the Strings the Thing summer music camps and shares Ron’s love for Celtic fiddling. The partners perform and teach under the banner Heritage Fiddlings with styles ranging from lilting Irish and foot-stomping Cape Breton to sonorous Gypsy.

Elizabeth studied with Jim Mendenhall at Brandon University. Jim founded Brandon’s Collegium Musicum and was its director for over 35 years. He also founded and conducted a Baroque chamber orchestra there and published numerous articles about Baroque music. His studies took him to the University of Vienna. (That makes three of us with a Viennese connection.)

When he retired to Kelowna, Jim brought several dozen period instruments with him. These are primarily double-reed woodwinds (bassoons and oboes), replicas of Medieval and Renaissance models. Many he built himself. He performs on a shawm, a rackett and four sizes of curtals. “The term curtal means short,” he explains. “Curtals are shorter than the bassoons.”

His Baroque bassoon and oboe are labeled D’amore. Italian crooner Dean Martin explained the word. “When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie … you’re in love.”

Jim Mendenhall

Jim explains the musical adaptation: “All D’amores have swollen sections in the tubing,” Apparently the musicians of yore had a sense of humour.

Jim also owns a 15th century viola da gamba. Also called a viol, this large stringed instrument might be mistaken for a cello because it too is held between the knees. But the viol has more strings, is tuned differently than a cello and the bow grip is backwards.

Susan Adams’ partner, Clive Titmuss, builds stringed instruments. He calls himself a lutherie, crafting lutes and guitars like those of 300 to 600 years ago. Delicate carvings decorate the bodies of his Renaissance and Baroque models. Recently he’s been working on four 16th century Spanish guitars, called vihuelas. The openings of these guitars are finished with exquisite lace rosettes tatted by Susan.

Richard Walker

The couple first merged their musical interests during their studies at the University of Calgary where they met Richard Walker whose specialty was horn performance. Richard furthered his experience with various involvements in England where he discovered natural horns. Returning to Canada in 1979, he taught music in Comox until he retired to Oliver.

“Playing instruments of the past gives me an appreciation for the extraordinary skills of past musicians,” he says. Like those pipes at St. Saviour’s, played by his partner, Christine Purvis, the sound of the horn also relates to the length and diametre of the tubing. By Mozart’s time, natural horns were common orchestral instruments. Richard’s horn dates to about 1830, before valves were added to create the modern French horn. “Without valves, pitch was varied through hand-stopping within the bell of the horn, but these movements are difficult to describe and difficult to perform. Playing a natural horn is tricky,” he says.

To keep the repertoire and techniques of these earlier musical eras alive, Clive and Susan have founded The Early Music Studio (www.earlymusicstudios.com). —Barbara J. Shave

Photos by Bruce Kemp; Ingrid Shellenberg photo by Sandra Copes