Okanagan entrepreneurs are making it big. What’s their secret?

Okanagan entrepreneurs are making it big. What’s their secret?

A dark-haired man stands over a vat of melting sugar. With each turn, the metal tub tosses an enticing scent into the air. Around the corner, a dozen 50-pound sacks of corn sit on the floor. Barry Stecyk’s black heels crunch on stray kernels.

Walking through the Hevy D’s Old Fashioned Kettle Korn factory, housed in a row of commercial bays near Coldstream, Barry looks up. Darren Hickson, the bear-like company namesake and vice-president, pulls a pen from behind his ear. “Dover called.”

Barry smiles and nods. “Good,” he says. “That’s good.”

The call is about a deal, says Barry, founder and owner of the Vernon popcorn company that’s competing with the likes of Frito-Lay and holding its own. He’s been getting a lot more of those calls lately. Major grocery chains want to carry Hevy D’s and Asian, Texan and Mexican firms want to wrap their labels around his gourmet popcorn.

But it wasn’t always that way. In 2005, Darren told his brother-in-law Barry about his recipe for a sweet but salty popcorn he thought people might like. Soon they were in business. “It’s been five years of a tough grind and shattered dreams,” says Barry. “You hear stories about the businessman on his last knee. Well, this is one of those stories.”

****

“An unlikely entrepreneur hub” is how the Financial Times described the Okanagan Valley in June 2011. In the UK, mused the writer, business thrives where people don’t. Think factories and bleak, concrete housing towers. Here, however, the landscape is painted with lakes, mountains, vineyards, and sun. Somewhere along the way the Okanagan became not just Canada’s Napa but maybe a sort of Silicon Valley, too.

Since 2009, two Okanagan communities—Vernon and Kelowna—have been named most entrepreneurial city in British Columbia by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. Its report, Communities in Boom: Canada’s Top Entrepreneurial Cities, considers government tax breaks and business owner’s optimism in addition to the number of start-ups and entrepreneurs.

It’s Robert Fine’s job to help steer and then tout these results. As executive director of the Central Okanagan Economic Development Commission (COEDC), Robert networks with entrepreneurs and politicians to make greater Kelowna a business-friendly area.

He says the Okanagan’s old identity did the advertising for its new one. “This has become a hub for entrepreneurs because talented and successful people want to live here.”

That becomes truer every year. According to Statistics Canada, both the population and the number of entrepreneurs have been on the rise for a while. The most recent available census data shows that between 2001 and 2006, Kelowna’s population increased almost 11 per cent while the city’s self-employed jumped from 11,685 to 13,755. In Vernon over those same five years, the population grew by seven per cent and the number of people working for themselves jumped by 315 to 4,200.

Not all of these entrepreneurs are outsiders who have recently moved to the region. Some grew up in the Okanagan and had perfectly good day jobs or a place in the family business when they decided to take the biggest risk of their lives.

Faith

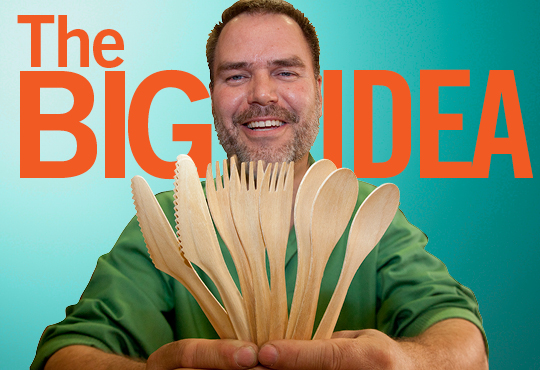

The Bigsby kitchen looked like a boneyard. Shards of wood shaved by knives lay everywhere, in mounds on the counter, in wet clusters in the sink and as flakes frying inside a waffle-maker doctored to bake the western birch.

“It used to take us four hours to make one piece of cutlery when we first started,” says Terry Bigsby. He’s now the president of Aspenware, a Lumby company that makes compostable wooden cutlery.

In addition to the shavings and several pairs of burnt oven mitts, Terry was joined in the kitchen by his father, Bob, and Claus Gerlach, all three shop teachers, and Mike Allen, an English and French teacher.

The foursome found themselves at the Bigsby home tinkering with firewood from the family farm after Claus saw a German television special about disposable wooden cutlery.

“You gotta see this,” he’d said.

Terry, whose Woodlinks course at Vernon Secondary School taught students how to make something out of wood and then sell it, watched the tape. Soon their team flew to Germany, met the inventor, declined his handsome price tag and returned home empty-handed. The group decided they’d would be better off making their own cutlery, and making it even better.

But there was no design, no press, no recipe. They had nothing but a kitchen, some wood scraps and eight hands. It was 1997.

“If someone would have told me it’s going to take $10 million and 10 years to do this, I would have said, ‘Jump in the lake,’” says Terry, who now heads Aspenware full-time. He raises his hand and, starting with his thumb, counts the hurdles of forming this company. Money is first. “We started with nothing,” he says. “Zero.”

In 2008, Terry appeared on CBC’s Dragon’s Den to entice the television investors. His cutlery got some great exposure, but everyone was “out,” as they say.

Aspenware struggled with start-up cash, and it battled—still battles—technical matters. They needed a mold, more molds, a plant. The spoon needed to be smoother. The knives needed to cut steak.

Each time Terry felt like throwing a fork in the fire, he looked 20 years beyond the blackened shreds in front of him and saw Aspenware on tables. “This will change the world,” he says, of the biodegradable flatware that rises from slash piles. “It’s healthy. It’s sustainable. It’s everything plastic isn’t.”

Today, Aspenware’s assembly line carves 50,000 utensils an hour, each a perfect, laminated two-ply piece of veneer bound with an edible adhesive, a model for which the company holds two patents. With his product now selling in stores like Home Outfitters, Pharmasave and Save-On-Foods, Terry dreams of Aspenware replacing plastic at every fast-food restaurant on the continent.

At Vernon Vipers games he sees kids sucking blue sno-cone ice onto their tongues with Aspenware spoons, and he smiles. “We could have given up years ago,” says Terry, but he’s thankful the group persevered.

****

Media exposure showcases the Okanagan’s natural attributes, even in times of tragedy. For weeks in the summer of 2003, Canadians saw footage of fires. Viewers felt terrible, but they also felt awe.

“Even more people came in,” says Robert Fine.

If those new residents couldn’t find work when they got here, they created their own. And if they made it, so did someone else.

Another of Robert’s theories about why the Okanagan has such a high concentration of entrepreneurs suggests the founding of one company spurs business for another, and another, and so on.

“Small business success breeds more business success,” he says, adding when outsiders move into the Okanagan and open shop, friends and colleagues catch on to the idea of relocating too. “They attract the people they do business with.”

Dominoes fall. The café serves a new regular. The printer designs a new sign. The tech shop on the corner connects new servers.

It was like this with what has now become Kelowna’s technology community. Two years after launching a snow-laden virtual playground for kids, online entrepreneurs Lane Merrifield, Dave Krysko and Lance Priebe sold Club Penguin to Disney for $350 million. More than 300 people still work at the Kelowna operation on Dickson Avenue, on the same side of the road as the Centre for Arts and Technology, Enquiro Search Solutions Inc., a Thai restaurant and a new coffee shop.

“That became a bit of an anchor for us,” says Robert. In Disney’s shadow, other gaming and technology firms are popping up and even relocating.

The face of the Okanagan, once stamped with manufacturing, forestry and agricultural industries, is different now. The first crack appeared when Kelowna’s Western Star Trucks shut its doors to 1,400 employees in 2002. In the fall of 2008, Lavington’s glass plant and Spallumcheen’s RV factory shut down; nearly 400 people lost their jobs. During those six years and beyond, several more businesses have shut their doors, mills are running with fewer staff and many of the survivors have stopped hiring.

“The economy has really changed the Okanagan,” says Ken MacLeod, a man who lives and breathes business. He’s a business consultant, runs his own group of companies, chairs the Okanagan chapter of a club for executives (TEC), is president of the Vernon Chamber of Commerce and, long before he felt the Valley’s pull, was once president and CEO of Canadian Tire. “People have been coming here for years for the lifestyle. Before the bust, it wasn’t difficult to make money in this community. You just had to work hard.”

Not anymore. MacLeod says the shift in the economy has forced a lot of people to become business owners, and a different kind of business owner.

“Some of them will do well and some of them will lose their shirt.”

Charity

Barry Stecyk and Darren Hickson started selling their sweet and salty gourmet popcorn under the blue awning of Walmart in Vernon. They worked the farmers’ markets too, shovelling Hevy D’s Old Fashioned Kettle Korn into little white bags as quickly as they could. Licking their lips, customers asked where else they could get it. Soon, grocery stores wanted shipments.

“We got to a place where it was like, go big or go home, and that was a really scary place to be,” says Barry. Houses were on the line. More than $1 million was needed to build the factory, hire staff, buy bags for packaging and fuel the trucks to drop the popcorn off.

They decided to go big.

In the beginning, Hevy D’s fell victim to wrongdoers, made some mistakes and tumbled into the red, but the company did raise a lot of money for charity. Barry was running a business, a new business in the snack industry, but Hevy D’s has always been committed to giving.

One hundred per cent of the proceeds from that entire first year in the Walmart parking lot went to 50 different Vernon causes. Hevy D’s went on to send cash to Haiti after the hurricane, sponsor a concert for Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan, and offer some of the proceeds of a special candy cane flavour to the BC Children’s Hospital.

“If we can use our popcorn to raise money and help people, we will,” says Barry, a former nurse whose family owns a care home for the mentally challenged in Vernon. For his charitable contributions the BC Country Music Association named him Humanitarian of the Year in 2011.

Amidst the fundraising, Barry has simultaneously been promoting emerging musicians, most notably with a Vancouver Province column featuring new artists and free music. It started with a benefit performance for the armed forces and led to free song downloads inside popcorn bags—a twist on the toy-in-a-Crackerjack-box approach.

“We pride ourselves on being ahead of the curve,” says Barry, who will soon release a Hevy D’s mobile application so popcorn and music lovers can discover new talent. “Marketing is number one on the list.”

Though it’s obviously working—the company makes about 75,000 bags a month for sale in stores ranging from Urban Fare to Overwaitea Foods across Canada—Hevy D’s’ marriage of popcorn and recording artists isn’t just a marketing technique. Barry loves music, and he loves seeing the little guy make it.

Last fall he was in an elevator in Vancouver’s Shaw Centre, on his way to the 25th floor where business tycoon Jim Pattison was about to offer distribution for Hevy D’s Old Fashioned Kettle Korn. The light reached 24, then 25. A bell dinged. The metal doors opened. Pattison was standing on the other side, holding out his hand.

Barry remembers the weight of his tongue. It took a moment, but he managed to speak and later signed the deal. “I can now say we’ve made it.”

****

Some have an idea but not a business plan. Some have a product but not a customer. Some pay more in rent than they could ever make in a month. Some just don’t want to work hard. Or they ask people to pay too little for that thing they’ve been toiling away at for weeks or even years, and they try to do too much, to be everything to everybody.

“I’ve seen a lot of failures,” says Ken MacLeod, looking out the window of a coffee shop on Vernon’s 32 Street, the stretch of Highway 97 where the sun bleats across the hoods of semi-trucks on their way south to Kelowna or Vancouver, or north and east, to Calgary. It costs Okanagan companies a lot to ship their product to the rest of Canada and beyond—if they can find customers outside the Valley. And that’s assuming they have enough skilled labour to make the product in the first place.

Despite that, or perhaps because of that, Aspenware president Terry Bigsby says there’s a good business atmosphere here. “There’s camaraderie. People want to work together to make things work.”

For Aspenware, which has been scouting sites for a second plant in Ontario, location is a catch-22. “We’re not in the middle of the fibre belt, but we’re in the middle of a culture of people who know about wood. We can afford to truck our wood, not forever, but a long way and still stay profitable. You make some decisions.”

Making tough choices and understanding everything about your business are just two steps on the ladder to success, says Ken. Today’s entrepreneurs in the Okanagan have to be good at branding, marketing and competing. “Now people have to be better business people, much more in tune to their business. The ones that survive are the ones that are really in tune with their market.”

There are survivors, and then there are virtuosos; those who want to own a business and those who have to. It’s in their blood.

Help

“Move that bus,” said Ty Pennington. The crowd hushed. Hearts pounding, they stepped closer to the screen, some sipped nervously at their drinks as they waited. Almost all of the three dozen Waterplay Solutions Corp. staff gathered at Kelowna’s Hotel El Dorado on March 6, 2005, had had a hand in building the water park about to be unveiled on TLC’s Extreme Makeover: Home Edition.

The camera panned through the new home of the Harris family whose sextuplets had seen Hurricane Ivan punch through their ceiling. Now, one of the boys was in the backyard. He clapped and his three-year-old body toppled on its way to the playground where his brothers and sisters were ducking, blinking and laughing as water squirted their ears and sprayed their faces.

“Truthfully, it was kind of emotional because it gave the kids something pretty unique and cool that most kids wouldn’t have access to in their backyard,” says Jill White, owner and president of Waterplay, a Kelowna company that has built more than 3,000 spray parks around the world. The Harris’s backyard park, which featured spraying bees, flowers and rings, was one of the more rewarding projects; so was the spray park the company made for a wheelchair-bound girl on a 2011 episode of the show.

Jill, who bought Waterplay in 2004 and has since helped the company become a global leader, is more at ease discussing that night at the El Dorado, the employees who were there, or the finish on a weld than her own work as an entrepreneur.

“I don’t like to talk about myself,” she says. “I like to talk about the team.”

Jill grew up in a house where talk at the dinner table was often about business. She was born a Thorlakson, a Tolko Industries forestry empire Thorlakson. In adulthood, after working for the family company, and elsewhere in accounting and in advertising, Jill heard about a Penticton-based spray park company whose owners were looking to sell.

She flipped through the catalogue, looking at the bright beams and hoses fashioned after animals. It was a business, but it was creative. It was decision time. She could continue to do what was as familiar as home, or she could go out on her own. Her mind was made up.

“The personality of the company really seemed to match me,” says Jill.

Waterplay grew. The company hired fabricators to do more building in-house. It moved into a 12,000 square-foot building and quickly filled the new premises—despite reservations among old employees. Jill says Waterplay’s success since then is because of her team, although her definition of team is a little different from other CEOs.

“There’s never going to be an executive washroom or parking lot. I’ll be the one unloading the dishwasher as much as anyone else,” says Jill. “I think the culture is something I’m most passionate about and most protective about.”

Employees have taken to her egalitarian approach. In December 2011, after tallying staff input, B.C. Business Magazine named Waterplay the province’s second-best manufacturing company to work for. This is success.

By Natalie Appleton

Photo by Doug Farrow